|

NetCDF Users Guide v1.2

|

|

NetCDF Users Guide v1.2

|

A netCDF dataset contains dimensions, variables, and attributes, which all have both a name and an ID number by which they are identified.

These components can be used together to capture the meaning of data and relations among data fields in an array-oriented dataset. The netCDF library allows simultaneous access to multiple netCDF datasets which are identified by dataset ID numbers, in addition to ordinary file names.

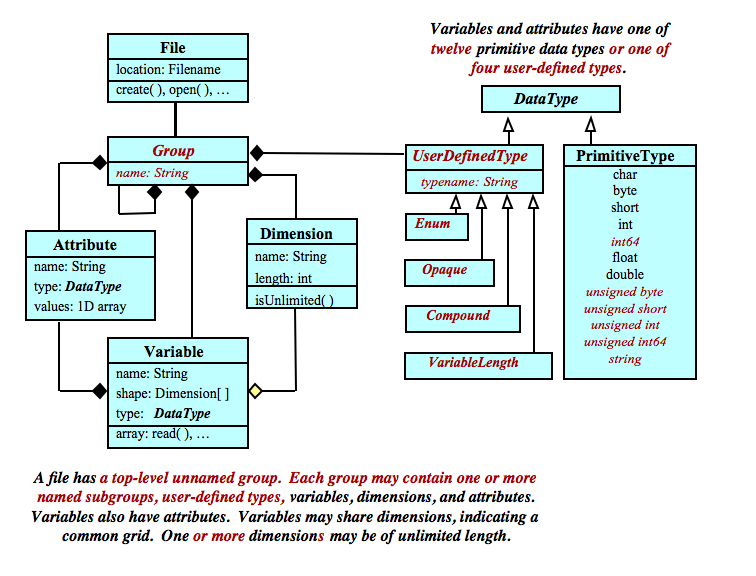

Files created with the netCDF-4 format have access to an enhanced data model, which includes named groups. Groups, like directories in a Unix file system, are hierarchically organized, to arbitrary depth. They can be used to organize large numbers of variables.

Each group acts as an entire netCDF dataset in the classic model.

That is, each group may have attributes, dimensions, user-defined types, and variables, as well as other groups.

The default group is the root group, which allows the classic netCDF data model to fit neatly into the new model.

Dimensions are scoped such that they can be referenced in all other groups. That is, dimensions can be shared between variables in different groups.

In netCDF-4 files, the user may also define a type. For example a compound type may hold information from an array of C structures, or a variable length type allows the user to read and write arrays of variable length values.

Types are also scoped such that they can be referenced in all other groups. That means, for example, that variables in different groups can have the same type.

Variables, groups, and types share a namespace. Within the same group, variables, groups, and types must have unique names. (That is, a type and variable may not have the same name within the same group, and similarly for sub-groups of that group.)

Groups and user-defined types are only available in files created in the netCDF-4/HDF5 format. They are not available for classic format files.

A dimension may be used to represent a real physical dimension, for example, time, latitude, longitude, or height. A dimension might also be used to index other quantities, for example station or model-run-number.

A netCDF dimension has both a name and a length.

A dimension length is an arbitrary positive integer, except that only one dimension in a classic netCDF dataset can have the length UNLIMITED. In a netCDF-4 dataset, any number of unlimited dimensions can be used.

Such a dimension is called the unlimited dimension or the record dimension. A variable with an unlimited dimension can grow to any length along that dimension. The unlimited dimension index is like a record number in conventional record-oriented files.

A netCDF classic dataset can have at most one unlimited dimension, but need not have any. If a variable has an unlimited dimension, that dimension must be the most significant (slowest changing) one. Thus any unlimited dimension must be the first dimension in a CDL shape and the first dimension in corresponding C array declarations.

A netCDF-4 dataset may have multiple unlimited dimensions, and there are no restrictions on their order in the list of a variables dimensions.

To grow variables along an unlimited dimension, write the data using any of the netCDF data writing functions, and specify the index of the unlimited dimension to the desired record number. The netCDF library will write however many records are needed (using the fill value, unless that feature is turned off, to fill in any intervening records).

CDL dimension declarations may appear on one or more lines following the CDL keyword dimensions. Multiple dimension declarations on the same line may be separated by commas. Each declaration is of the form name = length. Use the “/” character to include group information (netCDF-4 output only).

There are four dimensions in the above example: lat, lon, level, and time (see The Data Model). The first three are assigned fixed lengths; time is assigned the length UNLIMITED, which means it is the unlimited dimension.

The basic unit of named data in a netCDF dataset is a variable. When a variable is defined, its shape is specified as a list of dimensions. These dimensions must already exist. The number of dimensions is called the rank (a.k.a. dimensionality). A scalar variable has rank 0, a vector has rank 1 and a matrix has rank 2.

It is possible (since version 3.1 of netCDF) to use the same dimension more than once in specifying a variable shape. For example, correlation(instrument, instrument) could be a matrix giving correlations between measurements using different instruments. But data whose dimensions correspond to those of physical space/time should have a shape comprising different dimensions, even if some of these have the same length.

Variables are used to store the bulk of the data in a netCDF dataset. A variable represents an array of values of the same type. A scalar value is treated as a 0-dimensional array. A variable has a name, a data type, and a shape described by its list of dimensions specified when the variable is created. A variable may also have associated attributes, which may be added, deleted or changed after the variable is created.

A variable external data type is one of a small set of netCDF types. In classic CDF-1 and 2 files, only the original six types are available (byte, character, short, int, float, and double). CDF-5 adds unsigned byte, unsigned short, unsigned int, 64-bit int, and unsigned 64-bit int. In netCDF-4, variables may also use these additional data types, plus the string data type. Or the user may define a type, as an opaque blob of bytes, as an array of variable length arrays, or as a compound type, which acts like a C struct. (See Data Types).

In the CDL notation, classic data type can be used. They are given the simpler names byte, char, short, int, float, and double. The name real may be used as a synonym for float in the CDL notation. The name long is a deprecated synonym for int. For the exact meaning of each of the types see External Types. The ncgen utility supports new primitive types with names ubyte, ushort, uint, int64, uint64, and string.

CDL variable declarations appear after the variable keyword in a CDLunit. They have the form

for variables with dimensions, or

for scalar variables.

In the above CDL example there are six variables. As discussed below, four of these are coordinate variables (See Coordinate Variables). The remaining variables (sometimes called primary variables), temp and rh, contain what is usually thought of as the data. Each of these variables has the unlimited dimension time as its first dimension, so they are called record variables. A variable that is not a record variable has a fixed length (number of data values) given by the product of its dimension lengths. The length of a record variable is also the product of its dimension lengths, but in this case the product is variable because it involves the length of the unlimited dimension, which can vary. The length of the unlimited dimension is the number of records.

It is legal for a variable to have the same name as a dimension. Such variables have no special meaning to the netCDF library. However there is a convention that such variables should be treated in a special way by software using this library.

~~A variable with the same name as a dimension is called a coordinate variable. It typically defines a physical coordinate corresponding to that dimension. The above CDL example includes the coordinate variables lat, lon, level and time, defined as follows:~~

These define the latitudes, longitudes, barometric pressures and times corresponding to positions along these dimensions. Thus there is data at altitudes corresponding to 1000, 850, 700 and 500 millibars; and at latitudes 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 degrees north. Note that each coordinate variable is a vector and has a shape consisting of just the dimension with the same name.

A position along a dimension can be specified using an index. This is an integer with a minimum value of 0 for C programs, 1 in Fortran programs. Thus the 700 millibar level would have an index value of 2 in the example above in a C program, and 3 in a Fortran program.

If a dimension has a corresponding coordinate variable, then this provides an alternative, and often more convenient, means of specifying position along it. Current application packages that make use of coordinate variables commonly assume they are numeric vectors and strictly monotonic (all values are different and either increasing or decreasing).

NetCDF attributes are used to store data about the data (ancillary data or metadata), similar in many ways to the information stored in data dictionaries and schema in conventional database systems. Most attributes provide information about a specific variable. These are identified by the name (or ID) of that variable, together with the name of the attribute.

Some attributes provide information about the dataset as a whole and are called global attributes. These are identified by the attribute name together with a blank variable name (in CDL) or a special null "global variable" ID (in C or Fortran).

In netCDF-4 file, attributes can also be added at the group level.

An attribute has an associated variable (the null "global variable" for a global or group-level attribute), a name, a data type, a length, and a value. The current version treats all attributes as vectors; scalar values are treated as single-element vectors.

Conventional attribute names should be used where applicable. New names should be as meaningful as possible.

The external type of an attribute is specified when it is created. The types permitted for attributes are the same as the netCDF external data types for variables. Attributes with the same name for different variables should sometimes be of different types. For example, the attribute valid_max, specifying the maximum valid data value for a variable of type int, should be of type int. Whereas the attribute valid_max for a variable of type double, should instead be of type double.

Attributes are more dynamic than variables or dimensions; they can be deleted and have their type, length, and values changed after they are created, whereas the netCDF interface provides no way to delete a variable or to change its type or shape.

The CDL notation for defining an attribute is

for a variable attribute, or

for a global attribute.

For the netCDF classic model, the type and length of each attribute are not explicitly declared in CDL; they are derived from the values assigned to the attribute. All values of an attribute must be of the same type. The notation used for constant values of the various netCDF types is discussed later (see CDL Syntax).

The extended CDL syntax for the enhanced data model supported by netCDF-4 allows optional type specifications, including user-defined types, for attributes of user-defined types. See ncdump output or the reference documentation for ncgen for details of the extended CDL syntax.

In the netCDF example (see The Data Model), units is an attribute for the variable lat that has a 13-character array value 'degrees_north'. And valid_range is an attribute for the variable rh that has length 2 and values '0.0' and '1.0'.

One global attribute, called “source”, is defined for the example netCDF dataset. This is a character array intended for documenting the data. Actual netCDF datasets might have more global attributes to document the origin, history, conventions, and other characteristics of the dataset as a whole.

Most generic applications that process netCDF datasets assume standard attribute conventions and it is strongly recommended that these be followed unless there are good reasons for not doing so. For information about units, long_name, valid_min, valid_max, valid_range, scale_factor, add_offset, _FillValue, and other conventional attributes, see Appendix A: Attribute Conventions.

Attributes may be added to a netCDF dataset long after it is first defined, so you don't have to anticipate all potentially useful attributes. However adding new attributes to an existing classic format dataset can incur the same expense as copying the dataset. For a more extensive discussion see File Structure and Performance.

In contrast to variables, which are intended for bulk data, attributes are intended for ancillary data, or information about the data. The total amount of ancillary data associated with a netCDF object, and stored in its attributes, is typically small enough to be memory-resident. However variables are often too large to entirely fit in memory and must be split into sections for processing.

Another difference between attributes and variables is that variables may be multidimensional. Attributes are all either scalars (single-valued) or vectors (a single, fixed dimension).

Variables are created with a name, type, and shape before they are assigned data values, so a variable may exist with no values. The value of an attribute is specified when it is created, unless it is a zero-length attribute.

A variable may have attributes, but an attribute cannot have attributes. Attributes assigned to variables may have the same units as the variable (for example, valid_range) or have no units (for example, scale_factor). If you want to store data that requires units different from those of the associated variable, it is better to use a variable than an attribute. More generally, if data require ancillary data to describe them, are multidimensional, require any of the defined netCDF dimensions to index their values, or require a significant amount of storage, that data should be represented using variables rather than attributes.

The names of dimensions, variables and attributes (and, in netCDF-4 files, groups, user-defined types, compound member names, and enumeration symbols) consist of arbitrary sequences of alphanumeric characters, underscore '_', period '.', plus '+', hyphen '-', or at sign '@', but beginning with an alphanumeric character or underscore. However names commencing with underscore are reserved for system use.

Beginning with versions 3.6.3 and 4.0, names may also include UTF-8 encoded Unicode characters as well as other special characters, except for the character '/', which may not appear in a name.

Names that have trailing space characters are also not permitted.

Case is significant in netCDF names.

A zero-length name is not allowed.

Names longer than NC_MAX_NAME will not be accepted any netCDF define function. An error of NC_EMAXNAME will be returned.

All netCDF inquiry functions will return names of maximum size NC_MAX_NAME for netCDF files. Since this does not include the terminating NULL, space should be reserved for NC_MAX_NAME + 1 characters.

Some widely used conventions restrict names to only alphanumeric characters or underscores.

~~> Note that, when using the DAP2 protocol to access netCDF data, there are reserved keywords, the use of which may result in undefined behavior. See DAP2 Reserved Keywords for more information.~~

NetCDF classic formats can be used as a general-purpose archive format for storing arrays. Compression of data is possible with netCDF (e.g., using arrays of eight-bit or 16-bit integers to encode low-resolution floating-point numbers instead of arrays of 32-bit numbers), or the resulting data file may be compressed before storage (but must be uncompressed before it is read). Hence, using these netCDF formats may require more space than special-purpose archive formats that exploit knowledge of particular characteristics of specific datasets.

With netCDF-4/HDF5 format, the zlib library can provide compression on a per-variable basis. That is, some variables may be compressed, others not. In this case the compression and decompression of data happen transparently to the user, and the data may be stored, read, and written compressed.

The development of the netCDF interface began with a modest goal related to Unidata's needs: to provide a common interface between Unidata applications and real-time meteorological data. Since Unidata software was intended to run on multiple hardware platforms with access from both C and FORTRAN, achieving Unidata's goals had the potential for providing a package that was useful in a broader context. By making the package widely available and collaborating with other organizations with similar needs, we hoped to improve the then current situation in which software for scientific data access was only rarely reused by others in the same discipline and almost never reused between disciplines (Fulker, 1988).

Important concepts employed in the netCDF software originated in a paper (Treinish and Gough, 1987) that described data-access software developed at the NASA Goddard National Space Science Data Center (NSSDC). The interface provided by this software was called the Common Data Format (CDF). The NASA CDF was originally developed as a platform-specific FORTRAN library to support an abstraction for\ storing arrays.

The NASA CDF package had been used for many different kinds of data in an extensive collection of applications. It had the virtues of simplicity (only 13 subroutines), independence from storage format, generality, ability to support logical user views of data, and support for generic applications.

Unidata held a workshop on CDF in Boulder in August 1987. We proposed exploring the possibility of collaborating with NASA to extend the CDF FORTRAN interface, to define a C interface, and to permit the access of data aggregates with a single call, while maintaining compatibility with the existing NASA interface.

Independently, Dave Raymond at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology had developed a package of C software for UNIX that supported sequential access to self-describing array-oriented data and a "pipes and filters" (or "data flow") approach to processing, analyzing, and displaying the data. This package also used the "Common Data Format" name, later changed to C-Based Analysis and Display System (CANDIS). Unidata learned of Raymond's work (Raymond, 1988), and incorporated some of his ideas, such as the use of named dimensions and variables with differing shapes in a single data object, into the Unidata netCDF interface.

In early 1988, Glenn Davis of Unidata developed a prototype netCDF package in C that was layered on XDR. This prototype proved that a single-file, XDR-based implementation of the CDF interface could be achieved at acceptable cost and that the resulting programs could be implemented on both UNIX and VMS systems. However, it also demonstrated that Yeah providing a small, portable, and NASA CDF-compatible FORTRAN interface with the desired generality was not practical. NASA's CDF and Unidata's netCDF have since evolved separately, but recent CDF versions share many characteristics with netCDF.

In early 1988, Joe Fahle of SeaSpace, Inc. (a commercial software development firm in San Diego, California), a participant in the 1987 Unidata CDF workshop, independently developed a CDF package in C that extended the NASA CDF interface in several important ways (Fahle, 1989). Like Raymond's package, the SeaSpace CDF software permitted variables with unrelated shapes to be included in the same data object and permitted a general form of access to multidimensional arrays. Fahle's implementation was used at SeaSpace as the intermediate form of storage for a variety of steps in their image-processing system. This interface and format have subsequently evolved into the Terascan data format.

After studying Fahle's interface, we concluded that it solved many of the problems we had identified in trying to stretch the NASA interface to our purposes. In August 1988, we convened a small workshop to agree on a Unidata netCDF interface, and to resolve remaining open issues. Attending were Joe Fahle of SeaSpace, Michael Gough of Apple (an author of the NASA CDF software), Angel Li of the University of Miami (who had implemented our prototype netCDF software on VMS and was a potential user), and Unidata systems development staff. Consensus was reached at the workshop after some further simplifications were discovered. A document incorporating the results of the workshop into a proposed Unidata netCDF interface specification was distributed widely for comments before Glenn Davis and Russ Rew implemented the first version of the software. Comparison with other data-access interfaces and experience using netCDF are discussed in Rew and Davis (1990a), Rew and Davis (1990b), Jenter and Signell (1992), and Brown, Folk, Goucher, and Rew (1993).

In October 1991, we announced version 2.0 of the netCDF software distribution. Slight modifications to the C interface (declaring dimension lengths to be long rather than int) improved the usability of netCDF on inexpensive platforms such as MS-DOS computers, without requiring recompilation on other platforms. This change to the interface required no changes to the associated file format.

Release of netCDF version 2.3 in June 1993 preserved the same file format but added single call access to records, optimizations for accessing cross-sections involving non-contiguous data, subsampling along specified dimensions (using 'strides'), accessing non-contiguous data (using 'mapped array sections'), improvements to the ncdump and ncgen utilities, and an experimental C++ interface.

In version 2.4, released in February 1996, support was added for new platforms and for the C++ interface, significant optimizations were implemented for supercomputer architectures, and the file format was formally specified in an appendix to the User's Guide.

FAN (File Array Notation), software providing a high-level interface to netCDF data, was made available in May 1996. The capabilities of the FAN utilities include extracting and manipulating array data from netCDF datasets, printing selected data from netCDF arrays, copying ASCII data into netCDF arrays, and performing various operations (sum, mean, max, min, product, and others) on netCDF arrays.

In 1996 and 1997, Joe Sirott implemented and made available the first implementation of a read-only netCDF interface for Java, Bill Noon made a Python module available for netCDF, and Konrad Hinsen contributed another netCDF interface for Python.

In May 1997, Version 3.3 of netCDF was released. This included a new type-safe interface for C and Fortran, as well as many other improvements. A month later, Charlie Zender released version 1.0 of the NCO (netCDF Operators) package, providing command-line utilities for general purpose operations on netCDF data.

Version 3.4 of Unidata's netCDF software, released in March 1998, included initial large file support, performance enhancements, and improved Cray platform support. Later in 1998, Dan Schmitt provided a Tcl/Tk interface, and Glenn Davis provided version 1.0 of netCDF for Java.

In May 1999, Glenn Davis, who was instrumental in creating and developing netCDF, died in a small plane crash during a thunderstorm. The memory of Glenn's passions and intellect continue to inspire those of us who worked with him.

In February 2000, an experimental Fortran 90 interface developed by Robert Pincus was released.

John Caron released netCDF for Java, version 2.0 in February 2001. This version incorporated a new high-performance package for multidimensional arrays, simplified the interface, and included OpenDAP (known previously as DODS) remote access, as well as remote netCDF access via HTTP contributed by Don Denbo.

In March 2001, netCDF 3.5.0 was released. This release fully integrated the new Fortran 90 interface, enhanced portability, improved the C++ interface, and added a few new tuning functions.

Also in 2001, Takeshi Horinouchi and colleagues made a netCDF interface for Ruby available, as did David Pierce for the R language for statistical computing and graphics. Charles Denham released WetCDF, an independent implementation of the netCDF interface for Matlab, as well as updates to the popular netCDF Toolbox for Matlab.

In 2002, Unidata and collaborators developed NcML, an XML representation for netCDF data useful for cataloging data holdings, aggregation of data from multiple datasets, augmenting metadata in existing datasets, and support for alternative views of data. The Java interface currently provides access to netCDF data through NcML.

Additional developments in 2002 included translation of C and Fortran User Guides into Japanese by Masato Shiotani and colleagues, creation of a “Best Practices” guide for writing netCDF files, and provision of an Ada-95 interface by Alexandru Corlan.

In July 2003 a group of researchers at Northwestern University and Argonne National Laboratory (Jianwei Li, Wei-keng Liao, Alok Choudhary, Robert Ross, Rajeev Thakur, William Gropp, and Rob Latham) contributed a new parallel interface for writing and reading netCDF data, tailored for use on high performance platforms with parallel I/O. The implementation built on the MPI-IO interface, providing portability to many platforms.

In October 2003, Greg Sjaardema contributed support for an alternative format with 64-bit offsets, to provide more complete support for very large files. These changes, with slight modifications at Unidata, were incorporated into version 3.6.0, released in December, 2004.

In 2004, thanks to a NASA grant, Unidata and NCSA began a collaboration to increase the interoperability of netCDF and HDF5, and bring some advanced HDF5 features to netCDF users.

In February, 2006, release 3.6.1 fixed some minor bugs.

In March, 2007, release 3.6.2 introduced an improved build system that used automake and libtool, and an upgrade to the most recent autoconf release, to support shared libraries and the netcdf-4 builds. This release also introduced the NetCDF Tutorial and example programs.

The first beta release of netCDF-4.0 was celebrated with a giant party at Unidata in April, 2007. Over 2000 people danced 'til dawn at the NCAR Mesa Lab, listening to the Flaming Lips and the Denver Gilbert & Sullivan repertory company. Brittany Spears performed the world-premire of her smash hit "Format me baby, one more time."

In June, 2008, netCDF-4.0 was released. Version 3.6.3, the same code but with netcdf-4 features turned off, was released at the same time. The 4.0 release uses HDF5 1.8.1 as the data storage layer for netCDF, and introduces many new features including groups and user-defined types. The 3.6.3/4.0 releases also introduced handling of UTF8-encoded Unicode names.

NetCDF-4.1.1 was released in April, 2010, provided built-in client support for the DAP protocol for accessing data from remote OPeNDAP servers, full support for the enhanced netCDF-4 data model in the ncgen utility, a new nccopy utility for copying and conversion among netCDF format variants, ability to read some HDF4/HDF5 data archives through the netCDF C or Fortran interfaces, support for parallel I/O on netCDF classic files (CDF-1, 2, and 5) using the PnetCDF library from Argonne/Northwestern, a new nc-config utility to help compile and link programs that use netCDF, inclusion of the UDUNITS library for handling “units” attributes, and inclusion of libcf to assist in creating data compliant with the Climate and Forecast (CF) metadata conventions.

In September, 2010, the NetCDF-Java/CDM (Common Data Model) version 4.2 library was declared stable and made available to users. This 100%-Java implementation provided a read-write interface to netCDF-3 classic format files, as well as a read-only interface to netCDF-4 enhanced model data and many other formats of scientific data through a common (CDM) interface. More recent releases support writing netCDF-4 data. The NetCDF-Java library also implements NcML, which allows you to add metadata to CDM datasets. A ToolsUI application is also included that provides a graphical user interface to capabilities similar to the C-based ncdump and ncgen utilities, as well as CF-compliance checking and many other features.

Starting with version 4.1.1 the netCDF C libraries and utilities have supported remote data access.

To access (read or write) netCDF data you specify an open netCDF dataset, a netCDF variable, and information (e.g., indices) identifying elements of the variable. The name of the access function corresponds to the internal type of the data. If the internal type has a different representation from the external type of the variable, a conversion between the internal type and external type will take place when the data is read or written.

Access to data in classic formats is direct. Access to netCDF-4 data is buffered by the HDF5 layer. In either case you can access a small subset of data from a large dataset efficiently, without first accessing all the data that precedes it.

Reading and writing data by specifying a variable, instead of a position in a file, makes data access independent of how many other variables are in the dataset, making programs immune to data format changes that involve adding more variables to the data.

In the C and FORTRAN interfaces, datasets are not specified by name every time you want to access data, but instead by a small integer called a dataset ID, obtained when the dataset is first created or opened.

Similarly, a variable is not specified by name for every data access either, but by a variable ID, a small integer used to identify each variable in a netCDF dataset.

The netCDF interface supports several forms of direct access to data values in an open netCDF dataset. We describe each of these forms of access in order of increasing generality:

The four types of vector (index vector, count vector, stride vector and index mapping vector) each have one element for each dimension ofthe variable. Thus, for an n-dimensional variable (rank = n), n-element vectors are needed. If the variable is a scalar (no dimensions), these vectors are ignored.

An array section is a "slab" or contiguous rectangular block that is specified by two vectors. The index vector gives the indices of the element in the corner closest to the origin. The count vector gives the lengths of the edges of the slab along each of the variable's dimensions, in order. The number of values accessed is the product ofthese edge lengths.

A subsampled array section is similar to an array section, except that an additional stride vector is used to specify sampling. This vector has an element for each dimension giving the length of the strides to be taken along that dimension. For example, a stride of 4 means every fourth value along the corresponding dimension. The total number of values accessed is again the product of the elements of the count vector.

A mapped array section is similar to a subsampled array section except that an additional index mapping vector allows one to specify how data values associated with the netCDF variable are arranged in memory. The offset of each value from the reference location is given by the sum of the products of each index (of the imaginary internal array which would be used if there were no mapping) by the corresponding element of the index mapping vector. The number of values accessed is the same as for a subsampled array section.

The use of mapped array sections is discussed more fully below, but first we present an example of the more commonly used array-section access.

Assume that in our earlier example of a netCDF dataset, we wish to read a cross-section of all the data for the temp variable at one level (say, the second), and assume that there are currently three records (time values) in the netCDF dataset. Recall that the dimensions are defined as

and the variable temp is declared as

in the CDL notation.

A corresponding C variable that holds data for only one level might be declared as:

to keep the data in a one-dimensional array, or

using a multidimensional array declaration.

To specify the block of data that represents just the second level, all times, all latitudes, and all longitudes, we need to provide a start index and some edge lengths. The start index should be (0, 1, 0, 0) in C, because we want to start at the beginning of each of the time, lon, and lat dimensions, but we want to begin at the second value of the level dimension. The edge lengths should be (3, 1, 5, 10) in C, since we want to get data for all three time values, only one level value, all five lat values, and all 10 lon values. We should expect to get a total of 150 floating-point values returned (3 * 1 * 5 * 10), and should provide enough space in our array for this many. The order in which the data will be returned is with the last dimension, lon, varying fastest:

Different dimension orders for the C, FORTRAN, or other language interfaces do not reflect a different order for values stored on the disk, but merely different orders supported by the procedural interfaces to the languages. In general, it does not matter whether a netCDF dataset is written using the C, FORTRAN, or another language interface; netCDF datasets written from any supported language may be read by programs written in other supported languages. 3.4.3 More on General Array Section Access for C

The use of mapped array sections allows non-trivial relationships between the disk addresses of variable elements and the addresses where they are stored in memory. For example, a matrix in memory could be the transpose of that on disk, giving a quite different order of elements. In a regular array section, the mapping between the disk and memory addresses is trivial: the structure of the in-memory values (i.e., the dimensional lengths and their order) is identical to that of the array section. In a mapped array section, however, an index mapping vector is used to define the mapping between indices of netCDF variable elements and their memory addresses.

With mapped array access, the offset (number of array elements) from the origin of a memory-resident array to a particular point is given by the inner product[1] of the index mapping vector with the point's coordinate offset vector. A point's coordinate offset vector gives, for each dimension, the offset from the origin of the containing array to the point. In C, a point's coordinate offset vector is the same as its coordinate vector.

The index mapping vector for a regular array section would have–in order from most rapidly varying dimension to most slowly–a constant 1, the product of that value with the edge length of the most rapidly varying dimension of the array section, then the product of that value with the edge length of the next most rapidly varying dimension, and so on. In a mapped array, however, the correspondence between netCDF variable disk locations and memory locations can be different.

For example, the following C definitions:

where imap is the index mapping vector, can be used to access the memory-resident values of the netCDF variable, vel(NY,NX), even though the dimensions are transposed and the data is contained in a 2-D array of structures rather than a 2-D array of floating-point values.

A detailed example of mapped array access is presented in the description of the interfaces for mapped array access. See Write a Mapped Array of Values - nc_put_varm_ type.

Note that, although the netCDF abstraction allows the use of subsampled or mapped array-section access, there use is not required. If you do not need these more general forms of access, you may ignore these capabilities and use single value access or regular array section access instead.